Alan Sparhawk has always been a prolific, protean musician. A restless soul eager to explore unfamiliar sonic and psychic terrain. Though he’s obviously (and justifiably) best-known for his thirty years as frontman of the legendary band Low, a look at Sparhawk’s many side projects across that same span of time shows him experimenting with everything from punk and funk to production work and improvisation. Low itself never settled for a set sound or approach. The band was always a collaboration—a conversation, a romance—between Sparhawk and his wife, Mimi Parker, who was the band’s co-founder, drummer, co-lead vocalist, and its blazing irreplaceable heart. To take the journey from Low’s hushed early work, through the tremendous melodies of their middle period, all the way to the late lush chaos of their final albums, is to witness heads, hearts, and spirits in an act of perpetual becoming.

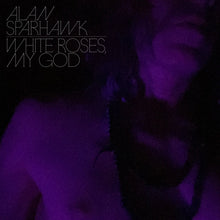

Parker passed away in 2022 after a long battle with cancer, and there is no question that WHITE ROSES, MY GOD is a record borne of grief. You can hear it in the title, as well as tracks such as “Heaven”, in which Sparhawk describes the afterlife, wrenchingly, as “a lonely place if you’re alone.” You can sense it too in Sparhawk’s decision to create this thing entirely on his own: every note, every lyric, every programmed beat. It would be reductive, even foolish, to see grief as the sole source or the final limit of this taut, brilliant, provocative, thrilling album, whose bold experimentation is powered by profound lyrics and propulsive beats.

Of the album’s composition, Sparhawk had this to say:

“The kids had the drum machine and a microphone set up in the studio. They’d have their friends over sometimes, and they’d record themselves taking turns free-styling. I brought them a synth and a voice pitch affect to have more options to mess with but before long, my curiosity won, and I found myself secretly stabbing around at possibilities with the unfamiliar tools, improvising, turning knobs until something would hit and a song would form. In hindsight, I can see now that it must have been what needed to come out of me, but at the time it felt like chaos and naïveté-even a little desperate. It kept tapping into a part of me that I’ve come to trust, so I kept recording.

“I found that the sounds and the rigidity demanded a certain structure, a framework, and I was trying to improvise songs within that framework. Which meant that the things that were organic had this freedom to be even more non-regimented. I really respect the moment when the music instigates transcendence. The vocals ended up being this very spontaneous, visceral engine. There’s a moment when something comes out of your mouth that you didn’t know was going to come out, and then it turns into something else. And something else. And it shakes you. Because what just came out was more precise and accurate and organized than anything you could have come up with. There’s magic in it because it is from the moment that it was created.”

“Can you feel something here?” Sparhawk asks on “Feel Something.” The line repeats over and over, evolving first into “I want to feel something here” and then “Can you help me feel something here?” Meanwhile the musical means he’s chosen to convey this message—especially the pitch-shifter—might seem at first like they’re making it harder to access that very something he wants us (and himself) to feel. Isn’t the vocoder a barrier between us and the deep emotionality we’ve long associated with an Alan Sparhawk vocal? Maybe, maybe not. Probably not. But even if it is, then it’s a barrier worth breaking and the music itself is the hammer. Sparhawk conjures forth the ghosts trapped inside these machines. WHITE ROSES, MY GOD is an exorcism whose purpose is not to banish the spirit but to set it free.

Trying to trace influences is a dodgy business, and fishing for comp titles is even worse. But let’s say you’re looking for forebears and fellow travelers to help situate WHITE ROSES, MY GOD. Just to start with a curveball, how about Childish Gambino, whose “Me and Your Mama”, Sparhawk has been known to cover live with The Derecho Rhythm Section, the funk quartet he plays in with his son? Or what about upstart weirdos extraordinaire 100 Gecs? Are those nods to fellow-Minnesotan Prince (maybe the Camille songs in particular?) in song titles like “Not the 1” and “Can U Hear”?

And let’s not forget Sparhawk’s regional compatriot, the great Neil Young. Forget the border for a second: from Duluth, it’s 150 miles south to Minneapolis, but it’s only 190 miles north to Thunder Bay, Ontario. There’s always been a healthy dose of Young in Sparhawk’s music—see for instance the Low+Dirty Three cover of “Down by the River”—but wait until you hear the next solo record after this one, recorded with Trampled by Turtles as his backing band and featuring a totally different arrangement of “Heaven.” WHITE ROSES, MY GOD might remind you of Young’s 1982 album, Trans, and if that sounds like a backhanded compliment then you probably haven’t heard it lately. Young recorded Trans in part as an homage to Kraftwerk; in part as a way to connect with his severely autistic son, whose love of computers helped him learn to communicate; and in part just to say, I don’t have to be who you think I am. Hell, I don’t even have to be who I think I am! Trans is a visionary record that has aged beautifully and buried its skeptics. So will WHITE ROSES, MY GOD.

In many ways WHITE ROSES, MY GOD feels like a hard break with the past, almost a debut. And yet there’s incredible continuity with Sparhawk’s past work and his traditional ways of working. He’s pathbreaking, yet again, invested as ever in the endless process of becoming himself. As he puts it on “Station”: “I can please myself with the things I seek out.” Us, too. We are lucky to be here to hear it as it happens.